The North Atlantic Ocean circulation system, responsible for Ireland’s relatively mild climate, has weakened, and is expected to weaken further in the coming decades with potentially disastrous consequences.

Strong ocean circulation has traditionally been associated with higher temperatures and sluggish circulation with cooler temperatures, but new research is challenging that view, asserting that weakened circulation could cause a surge in already rising global temperatures.

In an article published by widely-respected academic journal Nature, Dr Gerard McCarthy and Professor Peter Thorne, of Maynooth University’s Irish Climate Analysis and Research Units (ICARUS), analyse research by Professors Xianyao Chen of the Ocean University of China and Ka-Kit Tung of the University of Washington that challenges our understanding of how variations in a system of ocean currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) affects rates of global surface warming.

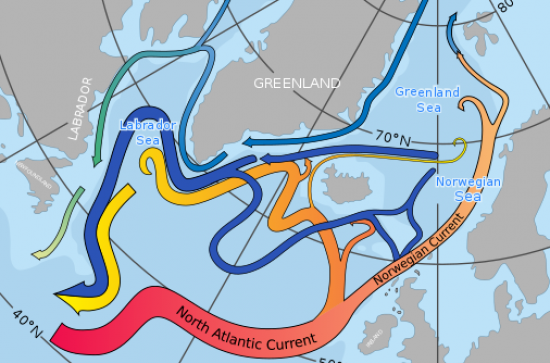

The AMOC is a system of currents stretching across the Atlantic Ocean that are generally characterized by a northward flow of warm water in the upper layers of the Atlantic and a southward flow of colder, deeper waters. The most familiar of these currents to Irish people is the Gulf Stream, which has long been widely recognised as protecting Ireland from extreme weather and giving the country its famous wet and mild climate.

On a global scale, the AMOC has conventionally been viewed as a vigorous force associated with elevated surface temperatures across the Atlantic Ocean, but this new research instead emphasises the role of the AMOC in taking heat from the surface and storing it in the deep ocean.

Global surface temperatures rose steadily from 1975 to 1998, but this growth slowed for 15 years – an event which gained popular attention as a ‘hiatus’. Since then, we have experienced the four warmest years on record; 2014 – 2017. Interest in this hiatus and what caused it has, therefore, waned considerably.

However, McCarthy and Thorne emphasize that because climate change is a complex response to slowly varying external factors, it is essential to re-examine and try to fully understand previous climate behaviour and its underlying causes. They argue that Professors Chen and Tung’s research may hold the key to explaining this hiatus, and that understanding the mechanics behind it can help us prepare for future climate change.

Atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases are increasing at an unprecedented rate, something which is widely understood as driving global warming. Chen and Tung contend that half of the heat arising from ever-increasing greenhouse gas concentrations is stored in the deep waters of the North Atlantic when the AMOC is strong, which reduces overall global warming.

The period in which a hiatus in global surface warming was observed is one in which the AMOC was robust and increasing in strength. That it could so effectively perform this function of transferring heat far beneath the ocean may explain the reduction in global warming.

Dr Gerard McCarthy explained why this matters for the future of global temperatures: “The AMOC has been deemed “very likely” to weaken in the coming decades. Indeed, the Atlantic Ocean has seen muted rises in surface temperature relative to the global ocean over the past few decades. This relative lack of warming has been interpreted as a fingerprint of AMOC decline.”

“Whether AMOC observatories will document the predicted decline remains to be seen, but they have already observed that the AMOC is in a weakened state and the Atlantic is surprisingly cold suggesting that it is not effectively storing heat in its lower levels.”

“Chen and Tung predict that such a weak AMOC will result in a period of rapid global surface warming that, if like the last similar period, could last for more than two decades. This in turn could have disastrous outcomes for the global climate and make navigating the challenges of global climate change even more difficult.”